En fortelling fra Bærum av Rune Christiansen

Et fotografiapparat av veldige dimensjoner

Østerås i morgentåke … et overdådig og gledelig gjensyn … utvisket skog … og i bakgrunnen – uværsskyer … og noe som spjæres … men likevel skinner de hvite blokkene … det synes som om alt i deg springer ut fra dette stedet … oppgangene med sin klang, treklyngenes tørre rasling, villaveiene … og trafikken – den svever … glir lydløst i retning av byen … som i en science fiction–film … og en buss stanser begivenhetsløst … du krysser Ovenbakken mot Niels Leuchs vei … en forvillet gresshoppe lander ute i fotgjengerfeltet … en pinefull kriger utenfor stridens rand … alt det som en gang var levende kommer deg i møte her … for første gang … for siste gang … og døden … den kommer deg i møte … i en annen historie … i snøen som lot vente på seg … forgjeves … du kan drømme om lykke … for eksempel … visst kan du drømme om lykke … og i denne drømmen bruker du nettopp det søtlatne uttrykket «lykke» uten at det er det minste beklemmende … du ser for deg at du er lykkelig bare den eller den omstendigheten er fraværende eller tilstede … barndommen henger ennå ved … barndommen vedvarer som den innbilte, ustadige lykkens abstinens … barndommen er til å ramse opp: borrer i en ullgenser, hester på et jorde, nypekjerner, Eiksmarka … men i en historie kan du ikke fortelle alt du vet … du kan ikke huske alt det som kom deg for øre … enkelte ting har ikke noen verdi mer … de sortmalte tallene på kjøkkenklokken … viserne av simpelt blikk … dessuten finnes det vel ikke noen egentlig historie … bare en rekke hverdagslige og tilfeldige foreteelser og sammentreff av den typen alle har opplevd på ett eller annet tidspunkt i livet … og den dypere meningen disse hendelsene måtte bære i seg er det opp til enhver å forstå og tolke som man selv finner det for godt …

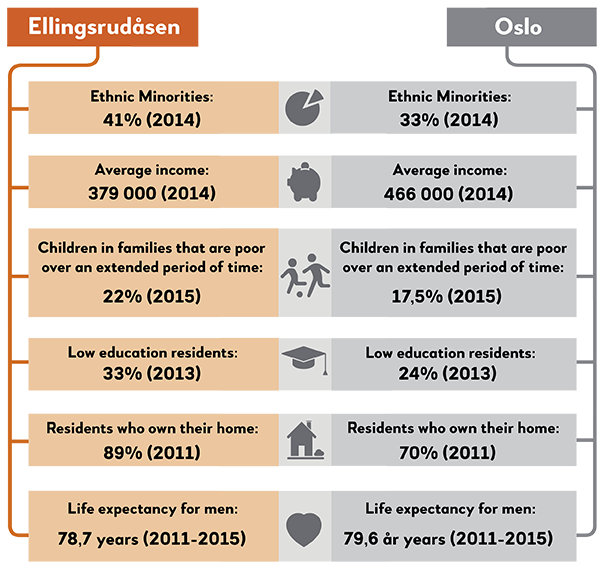

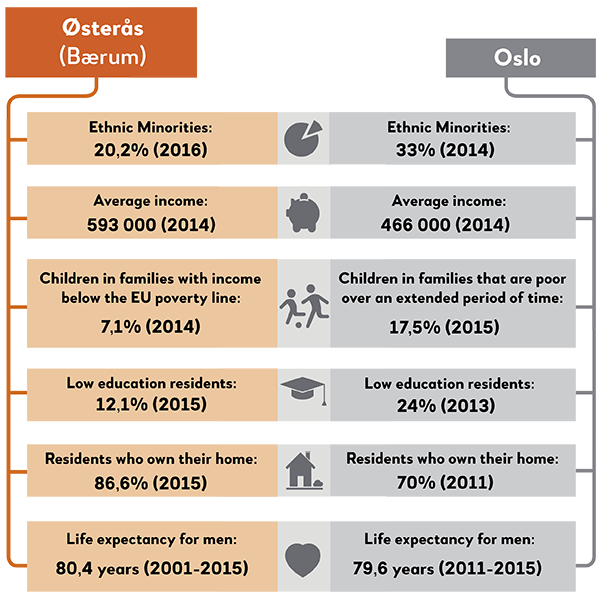

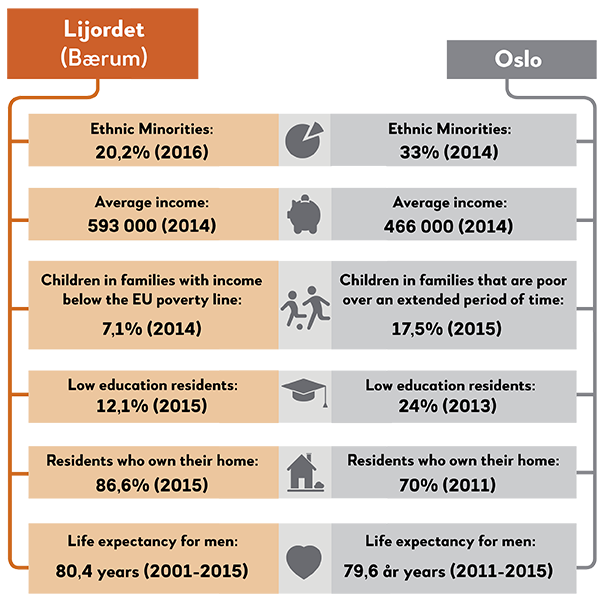

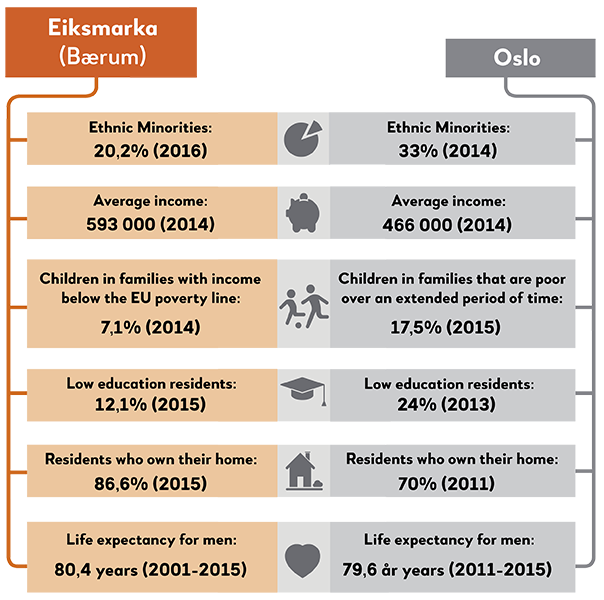

Except from some of the western stations on subway Line 3 to Kolsås, the three subway stations Østerås, Lijordet and Eiksmarka on Line 2 are the only ones that are situated outside the administrative borders of Oslo municipality. As areas of Bærum it's a bit hard to compare these with station areas at the eastern side of the municipaily border (the Oslo side). Firstly, due to the fact that the municipality Bærum does not create statistical material on the same comparable geographical level as Oslo. Secondly, and maybe more importantly, Oslo is, by Norwegian standards, a large city, while Bærum has a more rural character, which has made city researchers focus less on Bærum. While there are many Oslo based books and articles available that offer a thorough analysis of living standards, social inequalities, architecture, segregation, city developments etc, Bærum lacks such literature or studies, which constitutes a black hole in terms of such local knowledge. This may still seem strange for the following reason.

City research as a discipline has its roots in the US, and over there for decades the discussion on city outskirts and suburbia has been a central topic of interest, not at least how closely interconnected the city and suburbia is. In Norway, unfortunately, city researchers have not taken on this topic thread yet. Some expection, though, is the research by Per Gunnar Røe on, among other topics, Skjettenbyen (in Skedsmo) and the study by Bengt Andersen on migration between Oslo and Ski. Røe has also written extensively on “construction of places” and planning in Sandvika, the administrative center of Bærum. Or as Røe calls it; the “mini city” Sandvika. A relevance from this work is how Røe underlines how parts of Bærum close to Oslo, and across the municipality borders into Oslo, is in practical terms in fact one coherently built space or area. That implies that the area is in fact one joint belt of buildings and infrastructure, which enables, among other things, a “flow” of people across municipality borders. Bærum is as such an extension of the urban structures of Oslo. This results in Oslo citizens shopping in Bærum, or Bærum citizens working in Oslo.

Bærum is also a place many former citizens of Oslo move to, as well as others. The Masters thesis “Speaking tongues in Bærum” by Agnes S. T. Kroken, identifies how especially in the eastern parts of Bærum, in areas like Østerås-Eiksmarka, there are low ratios of locally born citizens, while in more western areas of Bærum more citizens are of local origins. Explanation for this is the proximity of the eastern parts of Bærum to Oslo. This again, she claims, affects the local identity of the population. Despite such a maybe “thinner” neighbourhood identity for the eastern Bærum citizens than the western Bærum citizens, the eastern citizens score better on other social economical indicators and overall on national tests. This may partly explain why young people in the eastern parts of Bærum, and thereby living closer to the western parts of Oslo itself, - often use a language with more “high status” endings of words (such as “-en”endings versus “-a” endings) compared to people living more towards the western parts of Bærum.

Travelling westbound on line 2, Lijordet is the second station when you enter the municipality of Bærum. It is also the second last station on the line. Øvrevoll Galloping Track is located near to the station. This galloping track is the only one in Norway. According to Wikipedia, Øvrevoll had its grand opening in the summer of 1932, by King Haakon VII and Queen Maud of Norway. In August the Norwegian Derby is held at Øvrevoll and one will find the yearly Hats Parade as a regular part of the programme. The residential property development, which started just after the end of World War II, was dominated by row houses, but was supplemented with detatched houses and smaller villas over time.

Lijordet is probably little known among people in the greater Oslo area – except for the ones living nearby, naturally. At the same time the municipality Bærum, and different areas within the municipality are well known in all of Norway. Often when one discusses stigmas and stigmatization of areas it is linked to crime rates and challenges with crime, exposed groups of inhabitants suffering from poverty or having social issues or other negative characteristics. Still, is it possible to discuss the stigmatization of more wealthy areas such as the ones in the most western parts of Oslo and more wealthy municipalities such as Bærum? Often, in literature, this is considered to be reversed stigma. Bærum experienced this in one of the most popular TV programmes in Norway in the mid nineties; Lille Lørdag. A comedy show which aired prime-time on NRK (the National Broadcasting Company). Lille Lørdag used the word ´Blærum´ as an insult when presenting the perception of Bærum people from more southern and less wealthy parts of Norway. Inhabitants in Bærum were presented as more cocky and pretentious with an upper class superiority, perceiving themselves to be better than the average Norwegian. The show presenting caricature that anyone from Bærum was like that.

A great deal of research has been conducted into these topics. For instance, one such study has examined the motives of people relocating to St Hanshaugen, it concluded that the projection of St Hanshaugen as a non-pretentious neighbourhood in Oslo, was in itself an effort to distance oneself from the stereotypes of Western Oslo as being affluent and bourgeouis (Eide 2013). One study looked into the motives of relocation among inhabitants in St Hanshaugen in Oslo, and they did find, among other things, that the telling of St Hanshaugen as a non-pretentious district in Oslo in reality was an effort to distance oneself from the stereotypes of Oslo west as rich and snobbish (Eide 2013). The narrative of St Hanshaugen as a ´district with diversity´and ´a district in the middle´ is, as well, built upon the understanding of a will to distance oneself both from the more caricatured displays of both the East-end and the West-end.

Research into resident’s sense of belonging to a district in Bærum shows that many of our sources experience a stigma associated with the area where they live. This stigma is connected to the idea of wealth and snobbery (Østerhus 2012). For people that move between different neighbourhoods in west Oslo and Bærum, the research found that this also applies to many of the more typical west-end neighbourhoods. Indeed, many of our sources did not wish to disclose where they came from or went to great lengths to cover up this information. Rather than say where they come from, they simply say that they live in Oslo when talking to people who are not local to the area. Many participants stated that their children were ashamed about saying where they come from when starting high school or meeting children from other neighbourhoods in Oslo. Others claim that their children have experienced bullying when participating in sport activities. As one of the local residents put it ‘the first few years, when I moved here, I found it rather embarrassing to live here´ and ´One thought that one did not want to be marked out, if you know what I mean´ (Østerhus 2012:p72). This might be a distinctly Norwegian social democratic characteristic at play or perhaps a more universal issue? In most cultures one can find that it is quite common to “kick upwards” towards the more affluent groups in society and where they live.

If you take the subway Line 2 heading westwards, and arrive at Eiksmarka, well then you have left Oslo. You are now in a different county and a different municipality. Eiksmarka is in Bærum municipality, which again belongs to Akershus county. Buildingwise Eiksmarka does not divert much from the areas you have already passed through. Villas and other “small houses” dominate the housing constructions. In these homes a total of around 4000 people live. The area resembles much the western parts of Oslo, by having more a suburbian than a city expression. The streets are relatively quiet, and during daytime on a weekday in the summer season, birds chirping is a familiar sound. For the families living there Eiksmarka is probably an “ordinary” residential area, or simply their place of home. For a social scientist on the other hand, Eiksmarka can be considered as a part of the Oslo regions more privelleged neighbourhoods. Compared to neighbourhoods like Tøyen or Lindeberg, on the more eastern parts of Oslo, people at Eiksmarka live (most often) in more expensive houses, the neighbours make more money, and there are as such also less poor families around. In 2015 the local newspaper Budstikka for example reported that among the most affluent inhabitants of the municipality, divided into postal code numbers, the top ten richest in Eiksmarka have fortunes of just below 40 million NOK. In an interview in the business newspaper ”Dagens Næringsliv” in 2015 a local real estate agent reported that Eiksmarka was among the “hottest” areas in Bærum for “people with high spending abilities”. Further, compared to the two areas east in Oslo mentioned above, the frequency of large gardens in Eiksmarka is far higher. If you ignore the municipality borders, Eiksmarka is practically an extension of the western parts of Oslo itself. As such, the area contributes geographically to confirm and maintain the rough social division into the affluent “half” where wealthy people live comfortably, while the others live more “exposed” on the other half of the city. Still, this is not necessarily the complete story of Eiksmarka.

Even if many are drawn to the attractive small house environment of the area, others also find the area too rural – despite the fact that Eiksmarka was the first place in Norway to get a shopping mall. It was here, in 1953, that the Norwegian shopping mall development started, and thus can be seen as the birthplace of a development trend that today has made Norway into a country with the highest density in Europe of such shopping malls. The idea behind the development of the shopping mall was to offer people indoor shopping options, as well as a wide range of shops and restaurants in a concentrated space. Today this may not be the first to come into your mind if you have visited or seen Eiksmarka Senter (architectonically it looks more like what is reffered to as a “strip mall“ in the US), but the new center is under development with apartments as well as shops, and soon only the mental memories will be left from the snackbar hangout in the 50’s and 60’s. Anyhow, some still think there is too much bird chirping and too many square meters of grass lawns on Eiksmarka. In an interview in “Aftenposten” a family lays out how they, just like many other families with small kids, moved out of the city to gain “more space and quiet surroundings”. On the contrary, they did not find the peace in these country-like surroundings. Rather than “oiling the terrasse or hatching ice on the drive way”, they wanted to go back to the urban life within the Ring 2 circle road around Oslo. So, they moved against the stream and back to the city.

En fortelling fra Vestre Aker av Mette Karlsvik

Frå ugras til gras

Ein båt ligg lågt i fjorden, er tung av gutar, gamlingar, gull og frø av aegopodium podagraria. Biskopen står på berg og tar imot brør og frø og priklar frøa; forsiktig, i bed ramma inn av stein. Dei plantar i rekkjer, med fem centi mellom kvart frø. Frø spirar; ein puls gjennom jorda. Gror opp for kvar femte centimeter, visnar, men kjem att våren etter. Ein puls gjennom åra: Kvar vår er skvallerkålen ny. Ynglar, reiser med vinden, og finn jord der andre ser by, grus, grøft. Podagraria slår rot der andre frø fér. Først fjorden, sidan opp bekken, og vestover, forbi furu, lauvskog. Langs togskinnene er ein æveleg bris av T-banevogner. Ugras klarar vind, svingar og skinnekvin. Skvallerkålen var jo planta; er kultivert. Han blir naturalisert, og tilpassar seg gjennom skiftande årstider, årtier. Aegopodium podagraria står sjølv når elektrisk tog susar forbi og gjennom låg lauvskog. Toget er berre ei humle som stoppar ved stasjonar: Slepp noko av, plukkar noko opp. Holmen møter Hovseter møter Røa, blandar blod og blomstrar. Byfolk sett bu på usannsylege stader. Alt er sivilisasjon så lenge toget går forbi. Tøff tøff over trefjøler. Fjølene ein puls under skinner av jern og skinnene ein navlestreng ein aldri klippar. Ikkje klipper ein graset eller sagar furuer. Nesle, ugras, ljå står i rekkjer langs lina. Vognene sig forbi; ein kvilepuls gjennom dagen.

The final destination on line 2 within the western borders of Oslo is Ekraveien. Line 2 then continues beyond the confines of Oslo to Bærum municipality. As well as being the final stop in Oslo, Ekraveien is also the smallest station on line 2. Ekraveien station is located close to Grinidammen, a popular local bathing spot in the Lysaker river. Ekraveien is also the station providing access to the Bogstad golf course.

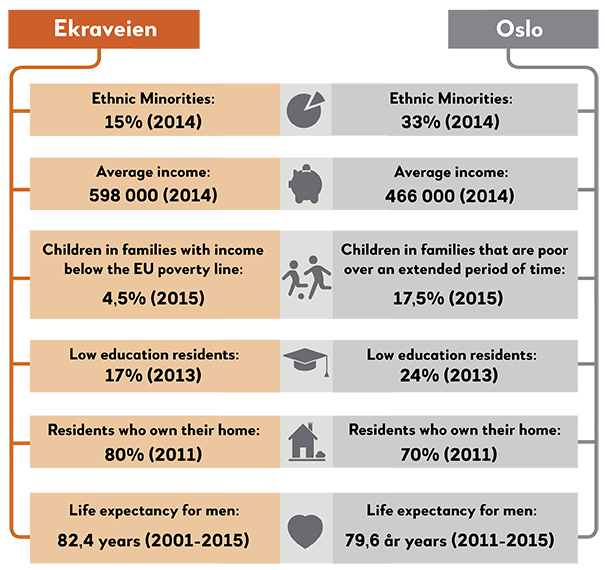

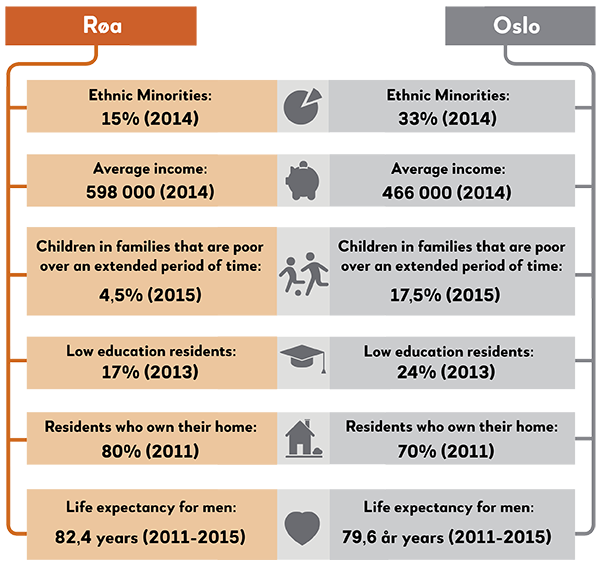

Ekraveien is part of the Røa neighbourhood, and scores very high on most living condition statistics, for example when it comes to percentage of inhabitants with low education, compared to the rest of Oslo. The presence of ethnic minorities is very low in the area, with 84% of the residents being recorded as ethnic Norwegians in 2016. The number of ethnic Norwegians rises to 88% when it comes to children under 17. This pattern is not unusual in neighbourhoods on the west side of the city, whilst for the ethnic minority population on the east side, this age structure is quite rare, where large families with numerous children dominate. In Røa though, the opposite is true. The fact that the three largest immigrant communities in Vestre Aker borough are Polish, Swedish and Filipino partly explains this pattern. From 2011 to 2015, the number of ethnic minority families with children born in Norway has decreased. Statistics show that both Vestre Aker as a whole and Røa have a far lower than average percentage of immigrants staying on a short term basis from non-western countries when compared to other neighbourhoods in Oslo. Research by Wessel found that the number of residents with a Norwegian background has increased proportionally in districts across the west side during the last 35-40 years, meanwhile residents with an ethic minority background has increased proportionally in neighbourhoods on the east side. The reason behind this phenomenon is that the composition of groups with different country backgrounds has changed, with large numbers of residents from ethnic minorities moving to the east side during the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s. From year 2000 and onwards this pattern is less apparent with some moving east and others to the west. Certain minority groups on the west side actually had a higher population in 1991 than 2011.

A study looking into migration patterns of ten ethnic minority groups in Oslo for the period of 1998 to 2008 using data at individual, household and neighbourhood level has revealed some interesting trends. They found that the only ethnic group on the western side of Oslo that has increased in numbers are families of Iranian origin. In the Vietnamese community we can see that they moved westwards as their income increased (Magnusson Turner & Wessel 2013). Very few of the other eight minority groups showed a tendency to move westwards, even in the case of an increased income and thus the economical possibility to do so. According to Wessel (2017), cultural capital plays a much greater role than economic capital in determining whether minority groups move towards west in the city. Well educated Indians, Iranians, Chinese and Vietnamese are among the few groups that increasingly have started their journey towards west.

The name «Røa» is the plural form of the Norwegian word “Rud” which originates from “Ryding” (clearance). According to the Oslo city encyclopedia the “Rød-gårdene” were divided into four farms already in the middle ages. In the19th century there was both farming activity and a sawmill in the area. The development of the area started from the 1920s and it formed a suburb when Røa became the last station on the so called “Røabanen” (The Røa line) in 1935. The construction of the Røabanen continued towards west and in 1972 the line reached all the way to Østerås in the Bærum municipality, which since then has been the last station on the western side of Line 2. The area was developed mainly with the construction of small houses. The Hare Krishna movement which belongs to the hindu bhakti tradition had also its gathering place at Røahagan in Røa.

After WWII it has been built quite a few row houses and apartment buildings, and the shopping area around the Griniveien/Vækerøveien crossing was also established. Røa center offers a good choice of shops, a bank, a “vinmonopol” (liquor store), a pharmarcy and a library. In the past decade, the urban densification accelerated with more apartment buildings and terrace row houses, and the area is still in a transformation phase with a mix of commercial and residential buildings that are either completed, in progress or planned. These changes have led to the fact that almost half of the residential buildings in the Røa neighbourhood were apartment buildings in 2016, meanwhile 37% were row houses/semi-detached houses, and only 16 percent were detached houses.

Røa is a stable residental area when it comes to living and moving frequency, and has a moving frequency which is half of that in e.g. Tøyen. Only one-fifth of the residences are for rental in Røa compared with half of the residences are such in Tøyen. In Røa less than 1% of the residences are for social housing compared to 9.5% in Hovseter (highest on the west side of Oslo) and 18% in Lower Tøyen. Overcrowding rate is also low in Røa and only 19% of residences have less than 1 bedroom per person, compared with 40 percent in Tøyen. Life expectancy rate is also far over Oslo’s average, and the poverty rate, unemployment rate and teens who don’t complete high school are all relatively lower than the average in Oslo and much lower than Tøyen.

For more than 100 years, the district has a strong culture in sports. Skiing, football, bandy and gymnastics are in focus since Røa Sports Club was established in 1990. The sports club have its own football fields and indoor sports arena. The women’s football team, the so called “Dynamite Girls”, has won multiple trophies over the last decades. Among the famous players it's worth mentioning Siri Nordby and Marie Knutsen, while in men’s cross-country, you'll find Martin Johnsrud Sundby who is known both nationally and internationally. Other famous names from Røa are such as earlier Progress Party leader Carl I. Hagen and the doctor, comedian and TV-celebrity Trond-Viggo Torgersen. After the neighbourhood merging in 2004 Røa had a population of 21 425 inhabitants.

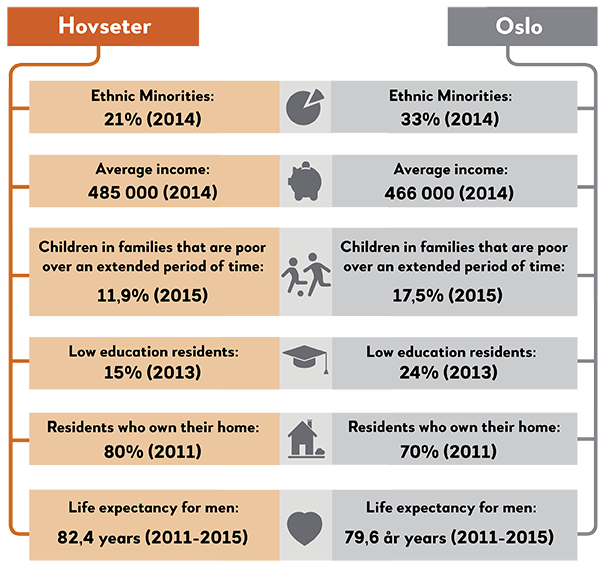

Is Hovseter a satellite town? Many would probably not consider this area close to Røa on the west end of Oslo as a satellite town, and it's rarely referred to as one. Still, considering the criteria ususally applied for a satellite town, it qualifies for most of them. Satellite towns are often seen as relatively large suburban housing estates built outside and on the edges of large cities. It's distiguished with an adequate share of high-rise residential buildings, comprehensively planned developments within a distinct defined area, and a place where both the inhabitants and the outside world consider it as a place. Satellite towns are typically built after World War II, and localised within a certain distance from the city centres. In Oslo, the Ring 3 circle road is often considered its border. Satellite towns often have a certain selection of public and private service institutions, but are closely connected to the city centers – in administrative, business and transportation terms.

In a study about how Norwegian satellite towns in Oslo, Bergen and Trondheim developed from the 1990 to 2000, 22 satellite towns where defined in Oslo, of which 21 are on the eastern side of the city, scattered in the area in between the Groruddalen valley, Østensjø and Søndre Nordstrand. Hovseter was the only area on the western part of the city defined as a satellite town. Of these large suburban housing estates in Oslo, Hovseter had by far the highest price level of housing and also the best reputation among the inhabitants in the city. Despite the fact that Hovseter resembles the large housing estates on the east side of Oslo in terms of physical qualities and composition of residents, the eastern estates have lower housing prices and a worse reputation. The most obvious explanation is simply the position of Hovseter on Oslo's west end, encircled by wealthy villa areas and very high housing prices.

The income level on Hovseter is by far the lowest of the neighbourhoods in the Vestre Aker borough. As a comparison the income level in the Slemdal neighbourhood, which has the highest level in the borough, is almost twice as high as Hovseter. The area also stands out from its neighbouring areas by a number of demographic and living condition aspects, and has by far the highest share of social housing on the west side of Oslo. The oldest high-rise building constructions were built by the Norwegian Airforce housing association towards the end of the 1940's, while the newer constructions were built by the OBOS housing cooperative in the mid 70's. In addition to several elementary schools, Hovseter also has a school for blind persons, a Rudolf Steiner school and an indoor sports center.

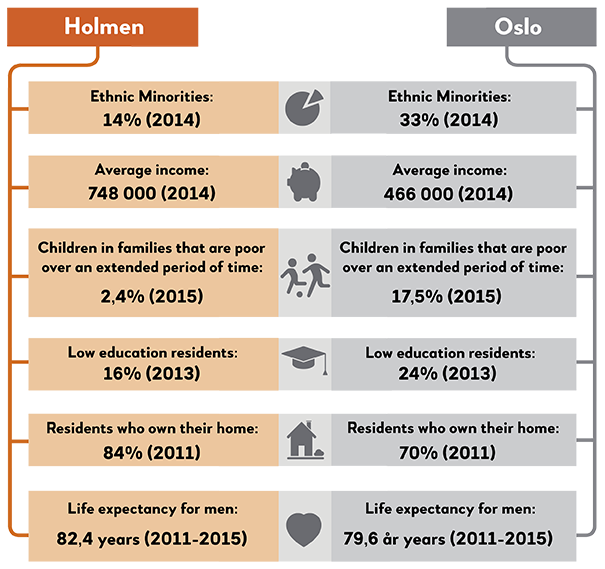

When one gets off the metro at Holmen station one is immediately stepping into a green residential district with rather large villas and spacious gardens. Holmen is a very privileged neighbourhood benchmarking near the top end against all the various indicators of living conditions. In comparison with the average in Vestre Aker – which is one of Oslos more affluent boroughs – the Holmen neighbourhood has higher scores for both percentage of people with lower education, percentage of people affected by poverty, number of people who are unemployed, life expectancy, number of people with disabilities and overcrowded living.

When it comes to the indicator ¨not completed upper secondary school´ both, Holmen and Vestre Aker, score equally well. Holmen is an area with very few people of ethnic minority backgrounds, particularly when it comes to people having lived in Norway for a short period of time.

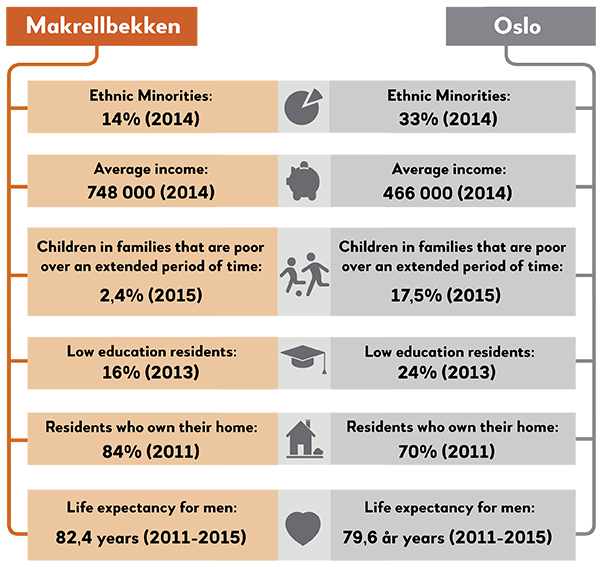

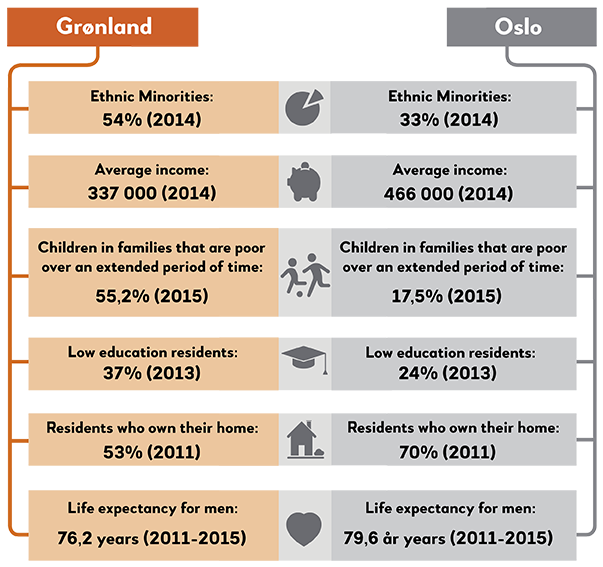

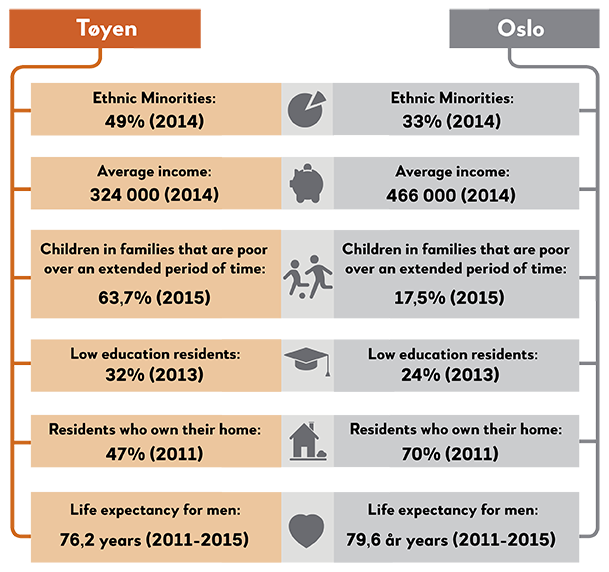

To grow up in a poor family over time, is very unfortunate for children and young people. The head count ratio of children growing up in families who are poor over a longer period of time in Norway was 10% in 2015 and 17.5% for Oslo. The variation between the different districts in Oslo is very high. The share varies from 2.4% in one of the neighbourhoods in the borough of Vestre Aker on the west side of Oslo, to 63,7% in one of the neighbourhoods in the borough of Gamle Oslo in the eastern part of the inner city. The neighbourhood in the eastern part has a share that is 26 times as high as the neighbourhood in the western part of Oslo, and the neighbourhood in the western part is actually Holmen. Holmen is the neighbourhood with the lowest child poverty ratio in the whole of Oslo, and between 2013 and 2015 this share has even been reduced. In the same period the child poverty ratio increased in most of the different districts in Oslo and in Norway as a total. Theses differences are seemingly being reinforced – since the areas with low ratios seem to have stable or lowering numbers while the districts with high ratios have an increase.

It is part of the overall picture that the Vestre Aker borough, together with the neighbouring Ullern borough, has the highest ratio of upper class habitants of all of Oslos districs, at the same time, they appear to profit most from neighbourhood-related benefits (Ljunggren wm 2017). Through an analysis of 28 different indicators, one found that the western boroughs clearly had higher score in the number of neighbourhood-benefits such as residential space, higher levels of school education, good dental health and a significantly higher life expectancy.

Makrellbekken is a residential area in the Vestre Aker borough on Oslo's west end. It is located between Smestad and Holmen. The sports hall Njårdhallen lies close to the station. A hall which in the 1960s and 70s functioned as a music venue for many international bands and orchestras. Even though the mackerel is a saltwater fish one could be forgiven for believing that the name Makrellbekken (the mackerel stream) derived from the fish, but that is not the case. According to the city lexica of Oslo there has been a linguistic transformation of the word Markskillebekken (the stream that divides grounds). A name indicating that the stream in the old days was the border between the farms Huseby, Voksen, Smestad and Holmen.

Husebyskogen (Huseby woods) is a popular recreational area for local residents. The Huseby military camp, “Gardeleiren”, is situated in the northwestern part of the woods and is the military camp of His Majesty the King´s Guards who frequently use the woods for training. In 2004 the Norwegian Armed Forces and the Ministry of Defence sold 40 acres of the southeastern part of the wood to the U.S. Embassy in Norway. The plan was to relocate the increasingly fortified embassy in Drammensveien away from the Royal Palace in central Oslo. The plans for setting up a new and highly fortified embassy building in the green lung at Huseby prompted a strong reaction in the neighbourhood, including the formation of an activists group - “Aksjon Vern Husbeyskogen” (action for the preservation of the wood) in 2005. Depsite this opposition, City Council won a ruling by a slender majority, that the embassy would be relocated to the wood. In response the activist group joined forces with Naturvernforbundet (Friends of the Earth), division Oslo and Akershus, to bring a civil court case against the Oslo Municipality with the objective of stopping the plans for the embassy. The civil action resulted in an appeal to the Supreme Court which they lost in 2009. Huseby became the new home of the U.S. Embassy to Norway and opened in May 2017.

It's easy to understand why residents fought to protect their green areas being replaced by high fences and a strongly fortified institution. It can be seen as a good example of “NIMBY” (Not In My Back Yard) where residents fight against changes they see as detrimental to their neighbourhood. This type of local engagement is often the result of major structural changes such as developments that affect the local environment, noise pollution, air pollution, major roads, institutions for people with mental illness or addiction problems. Everyone can agree that these institutions are important and necessary, but few would choose to have one on their doorstep.

The NIMBY phenomenon has often been linked to the injustice of poorer and less resourceful areas, with already a high number of challenges and burdens, and limited possibilities to fight against such changes, while neighbourhoods with higher social, cultural and economic resources among the inhabitants, and few burdens, often manages to block these kinds of developments. The Vestre Aker borough and the neighbourhood around the Huseby woods is a very privileged area in Oslo. In comparison with many other boroughs in the capital, this area has a strong majority of upper class residents benefiting from a high number of neighbourhood amenities and very few neighbourhood burdens (Ljunggren 2017). From this point of view, and knowing that these neighbourhoods often manage to stop this kind of negative changes, this could be considered a victory when it comes to sharing of burdens in Oslo. For once it was not a neighbourhood in east Oslo, but a neighbourhood in west Oslo, despite fierce opposition, that had to accept what many perceive as a burden in their own backyard.

En fortelling fra Ullern av Sverre Henmo

Alle veier fører til Borgen

Smestad er et veikryss mange har hørt om, noe som er ganske merkelig. Det er ingenting som skjer, og det er ingenting å se på. Alle er på vei forbi, igjennom eller bort. Over Smestadkrysset er det lange køer med biler, mens busser og T-baner skjærer igjennom på kryss og tvers. Alt lagt opp til at folk skal bort. Det er aldri noen som går av. Alle vil videre. Smestad er stasjonen der Kolsås-banen og Røa-banen møtes og kjører i flettemønster videre mot byen. Man trenger ikke kunne rutetidene, det kommer uansett snart en bane. I tillegg går det busser i alle retninger, og skulle det skjære seg, er det naturligvis en taxi-holdeplass rett ved siden av. På byens beste sykkelveier suser syklistene fra Røa og Bærum forbi på vei til eller fra sentrum. En fyr prøvde å lage kaffebar, men ga opp etter noen måneder for ingen stoppet lenge nok til å gå innom. Om formiddagen er det ingen som skal noe på Smestad. Bakkekroa ligger som et tomt og ensomt fuglerede og ser ned på køene i et kryss som merkelig nok assosieres med penger og status. Samtidig sitter de lokale i husene og blokkene og sverger på at de aldri skal flytte. For det er verdens beste sted å bo. Når de skal si hva som er bra, er det at det er lett å komme seg videre, det er stille om kveldene og trygt på skoleveien. Husene er 100 år gamle og det ligger en andektig ro over eplehagene.

Men bare ett T-banestopp nærmere byen ligger Borgen som inngangen til Vestre Gravlund. Det er Norges største gravlund. Der samles hver formiddag store, mørke flokker av sørgende som beveger seg med tunge skritt mot kapellet. Man kan ikke snakke høyt på Borgen. Alt foregår i dempet respekt for at de som står i nærheten sannsynligvis er i sorg.

Så blir det kveld og de lokale siver ut av husene for å gå tur. Da går man stille og rolig gjennom gravlunden der de etterlatte tenner lys på gravene, mens ungdom står i utkanten og famler seg fram. Og alle kjenner på tyngden fra de døde, uten å klare å ta inn over seg hvor kort det varer alt sammen.

For alle beveger seg bort fra Smestad. Men uansett hvilke veier vi velger, ender de fleste av oss uansett til slutt på Borgen. 700 meter og et liv unna Smestadkrysset. For alle veier fører til gravlunden.

If you travel on Line 2 you will find Smestad between the stations of Makrellbekken and Borgen. In terms of architecture these areas are quite similar in style. The landscape is dominated by villas with private gardens. The municipality of Oslo is currently planning to densify the housing communities in the area, especially around Smestad subway station. Which would imply a more “city like” expression of the physical environment.

Far back in time, during the High Middle Ages, the area was far less urban than now, when Smestad belonged to the monestary of Hovedøya island. After this period the land area was owned by Kronen (the Crown), and later on sold, during the late part of the 1600s. The farm became a self owned land farm in year 1700. The same year as Titanic sank, in 1912, Smestadbanen (the Smestad railwayline) was built, and the old farm land became a residential villa area. Even before the construction of the railway there were some houses on Smestad, but, as described in volume 4 of the book “The history of Oslo city” by the author Kjeldstadli, the railway stimulated further development. Smestadbanen was a so called suburban railwayline, which went from Majorstua to Smestad, and later was expanded to Røa in 1935, changing the name to Røabanen (the Røa line) with its expansion. Majorstuen was the eastern end of the line until 1928, when Valkyrie plass and Nationaltheatret stations were included as a part of the railway network. Only in 1987 the network was further expanded to include Stortinget station, and in 1997 the line was upgraded to a so called subway standard. Prior to this the line used an air born electrical operative system, and the wagons were actually trams made out of wood. While the subway system in Oslo today is owned and operated by public municipality owned companies, it was actually a private company called AS Holmenkollbanen that first developed the Smestad line. Like many of the other small house villa areas on the west side of Oslo it was no coincidence what kind of housing that was set up. During that period the area belonged to the municipality of Aker, outside the city borders of Oslo (the border was at Majorstuen), which at the time was named Kristiania.

In the Masters thesis “Prefab houses and villa constructions on the land area of AS Holmenkollbanen around 1895 to 1900” the author Hvidsten portrays in detail how the villa area was developed and which rules that regulated the development, the architecture, and the social construction of the population. To attract city dwellers to settle in on this more rural area the villas were promoted as a part of a planned holistic development. As described earlier the development and its content was strictly regulated. There were, among other regulations, defined minimum distance rules between housing and the roads, which made space for gardens in front of the houses, and similar rules applied for distances between each house and the neighbouring land property, as well as the size of each house. Further, housing for “workers” was not allowed to be built. Such regulations “controlled” which social groups got access to the villa areas. If and to what extent such regulations applied specifically to the villa development at Smestad is not known exactly to the city historians, but just like along the subway line Holmenkollbanen (which also developed Smedstadbanen) these villa areas became inhabited by “the wealthy”, described by the author Myrhe in his contribution to the anthology “Oslo – the city of inequality”.

Until World War II, the development of the suburban areas in Oslo was run by private enterprises, and whether the creation of a “divided city” was part of a planned continous process or not remains unclear. Anyhow, the development of large “houses” in a coherent villa area in the western suburbs of the city contributed to the foundation of today's “vestkant”, the “west end”. To what extent the current densification plans or “transformation” of certain villa areas will lead to architectonical changes and a rise in population is still unknown, as well as how this may affect the well-known current social geography of the area. What is for sure though, is that the current municipality plans creates a lot of local discomfort and uncertainty. In a public meeting, arranged by the municipality plan and building unit, the reaction from a local resident was clear: “This in one of the most beautiful small villa areas in the city. What's going on is a tragedy.”

Borgen is located in the district of Vestre Aker. The name is from an old Norse term, “byrgin”, that consists of the two words borg (castle) and vin, which translates to "natural meadow". There are still numerous meadows in the area today, in the sense that Borgen is dominated by small houses with relatively large gardens. This residential area is located just off the Frogner Park and other similar areas, like Vinderen and Smestad.

To an outsider, Borgen is a rather quiet place. Although the geographical distance to Majorstuen is short, Borgen is a rural area compared to the much more urban Majorstuen, which is located just one stop away from Borgen towards the city center. Another element that emphasizes Borgen’s reputation of tranquility is that the region rarely is featured in Norwegian newspapers, except when an interviewee happens to be located there - as in the case of a pop artist who recently spoke about moving there with her husband and their children. The peacefulness of the region was also the reason why another 30-year-old woman relocated here with her family: "We moved because the schools in the area have a good reputation". She also highlighted the short distance to The National Theatre, where she worked, as well as having family members residing just a few minutes away. Close proximity to school and/or family is a common reason for people to move to this area.

A man in his forties, however, declared that he and his family had picked this neighbourhood by coincidence. He described the area as "rural, quiet and calm, but very central". His impression of the social composition seemed to be consistent with the official statistics: "Actually, only my closest neighbours have approached me. They are nice and ordinary people. This is one of the more expensive areas in town, and I guess that’s an indication of what kind of people you will find here. Amongst the few non-Norwegians I’ve spotted are the au pairs who work nearby. Other than that, I’ve only seen Norwegians here.” Furthermore, he spoke about a development that might interfere with the "quiet" impression many people have of Borgen and other small towns in Oslo: "There is pressure on the housing market in Oslo, and especially in areas like Borgen. Typically, entrepreneurs purchase large plots with old detached houses and then build semi-detached houses or small detached houses. Densification seem to be a trend here. So the real estate market here attract people who are looking for a place to reside, but also entrepreneurs who are looking to further develop and construct new buildings." What this densification trend means for Oslo's villa neighbourhoods and those who live there, as well as the city's character as a whole, is hard to say. Certainly, many Oslo citizens dislike this expansion, while many politicians, developers and probably a number of potential home buyers, welcome it.

En fortelling fra Frogner av Roskva Koritzinsky

Uten Savn

Leiligheten ligger på Vestkanttorvet. Rommet vrir seg mot trærne, rommet strekker seg mot lyset. Ja, sier jeg, og signerer kontrakten. Så bor jeg her, alene. Jeg har en madrass på gulvet og et speil på veggen. I denne skrale friheten skriver jeg til deg. Om natten drømmer jeg at papirbunken slippes ned fra verandaen og deiser i bakken før arkene sliter seg løs. Som hvite fugler flyr de lavt over grusbanen; det er lett å bli romantisk på denne kanten av byen, og særlig når man har tilbragt hele livet andre steder.

Det er april og markedsdag på torvet. Jeg går mellom bodene og kikker på gamle møbler og avlagte klær, porselensdukker og landskapsmalerier. Det er knapt mennesker på her ute, på grunn av påskeferien eller den plutselige kulden – sola varmer ikke det minste, bare lukten av nystekte vafler gir den skarpe lufta mykere kanter. I hjørnet av plassen sitter en gammel kvinne tilbakelent i en klappstol, stolt og døsig som en dronning. Hun er tungt sminket, har gullkjeder rundt halsen og et fargerikt sjal på hodet. Som om hun har ventet – på meg eller bare på noen – ser hun rolig opp og møter blikket mitt. Hun smiler. Hun har en kortstokk i fanget, nå løfter hun den opp og sprer kortene ut i en vifte. Hun nikker spørrende mot meg. Jeg snur ryggen til, løfter opp et kobberarmbånd og later som jeg vurderer å kjøpe det. Jeg kjenner blikket hennes i ryggen. Hvor mye koster det? Mannen bak boden mumler fram en sum, jeg hører ikke hva han sier, det er ikke viktig. Jeg legger armbåndet fra meg og snur meg. Hun ser på meg fremdeles.

Spåkonen legger de kalde hendene sine over mine varme. Hun ser meg inn i øynene. Jeg tror på alle som tror, der har vi svakheten. Hun stokker bunken. Uten å trekke et eneste kort, ser hun på meg og sier: Du har gått fra noen som elsket deg. Jeg nikker. Hun rynker brynene, men bare et øyeblikk, før hun vifter med den ledige hånden i luften. Sånt skjer hele tiden, klukker hun. Det er en del av det å være ung, du skal ikke ta det så alvorlig. Jeg vil reise meg, men da griper hun tak i håndleddet mitt. Ikke gå, sier hun. Det lyder som en advarsel. La oss først se på skjebnen din. Jeg synker ned på bruskassen igjen. Hun trekker to kort og legger dem på låret mitt med baksiden opp. Hun vender det første. Tårnet, hvisker hun og stryker fingertuppen over den glatte overflaten. Og så, uten å snu det andre, ser hun meg inn i øynene: Syv sverd.

Etterpå går jeg nedover mot Elisenberg. Gatene er folketomme. Jeg følger Bygdøy allé et stykke, tar til høyre inn Niels Juels gate, til venstre i Svoldergata, alle disse navnene og stedene jeg ikke forbinder med noe eller noen; jeg har ingen venner her, ingen familie.

En dør slår tungt igjen. Høye hæler over brosteinen i en av bygårdene jeg passerer. Musikk fra et halvåpent vindu. Så stillhet. Byen virker utmattet, søvning, som om det var den som hadde ferie fra menneskene og ikke motsatt. Den puster ut i fraværet.

Jeg setter meg på en av benk i Framneshaven. Det trekker og trekker fra havet. Selv de minste steder kjenner man bare en flik av. Jeg lukker øynene. Jeg kniper øynene sammen. Jeg ser for meg tårn og sverd og noe som brenner. Jeg ser for meg noe som bare eksisterer når det brenner, noe som ikke fantes før det brant. Jeg trekker pusten. Jeg legger hodet fra meg. Jeg er ingen; jeg er uten savn.

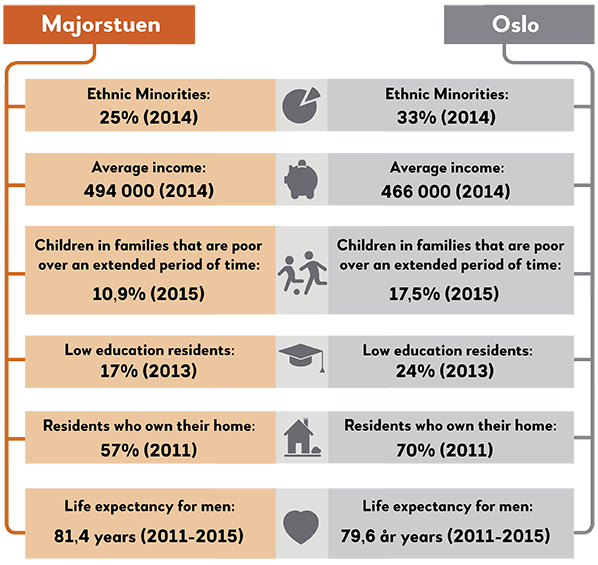

Today, Majorstuen is a place where Oslo people live, work, shop, enjoy themselves, and relax. It’s also the area where Oslo's most famous (and possibly finest) park, Vigelandsparken (The Frogner Park) can be found. Adjacent to the park is Oslo's largest outdoor swimming pool, Frognerbadet. Right next door lies one of the most famous cinemas in the city, and probably the whole country, The Colosseum, which was finished as early as in 1928. Within walking distance of Majorstukrysset – The Majorstuen Junction, you will find the home of Norway's most famous couple, the king and queen. The area also houses another well-known institution, the NRK (the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation). In other words, there are a number of well-known and well-loved buildings, facilities and institutions in Majorstuen. It should also be mentioned that the University of Oslo (also called Blindern), is located only a few steps away from Majorstuhuset, where you can find the area’s metro station and tram stop. It is also in close proximity to the country's most famous hospital, Ullevål. Furthermore, one of the city's most "flamboyant" areas is the neighbouring Homansbyen, just behind The Royal Palace. Here you will find, among other things, the magnificent villa The Uranienborg Castle * (built in 1885), designed by the architects Bernhard Steckmest and Paul Due. Due was one of the architects who shaped the city of Kristiania and, subsequently, Oslo (see "The history of Oslo City"). And it's no coincidence that it is in Majorstuen and other areas in the west that you will find the finest parks and the most spectacular buildings, as these are the homes of both the country’s and the capital's elites.

With its classic townhouses, great shopping facilities, historic charm and large parks, Majorstuen is a popular and relatively expensive area to live in. In January 2017, Krogsveen reported that the square meter price at Frogner was approaching 88,000 NOK, while the average for Oslo was about 70,000. On the east side the square meter price could be as low as 45,000, almost half of what one would have to spend in Frogner. Although it is popular to live in Majorstuen, there are also some who choose to move away. One such person is 80 year old Karen. She recalls looking for a house in the 1960s, with her husband and her three children. They came across an ad that said "Large apartment for sale at Majorstuen." With its 500 square meters, it was very spacious, but also very expensive. Nevertheless, they bought the apartment, and stayed there for many years. The grown-ups had many parties and the children had a lot of visitors. "It was an open house, and it was very nice" she says. The children have remained in the same apartment building, but when Karen’s husband got seriously ill, the old apartment was not suitable for her and her spouse any longer. Therefore, they sold the apartment and moved a couple of subway stops away, to a smaller place on the ground floor. Like so many others, Karen feels a sense of attachment to her side of town. "This is the environment we belong in." she says.

En fortelling fra Sentrum av Aslak Borgersrud

Gata som slukker sult og sorg

Ko. Ko. Ko. Ko. Gratulerer med dagen. Ko. Ko.

Det store elghodet (eller var det kanskje et kuhode?) snudde på seg. Ut fra sin faste plass på veggen. Med nesa ut mot rommet sa den de store ord, med sin rare, mørke stemme.

Det kunne vært en scene fra Tramteatret eller noe, men det var virkelighet. Jeg, søskna mine og morra mi var på restaurant. Og det var jeg som hadde bursdag. Vi lo. Jubla. Ropte ut, så hele restauranten blei flau, sikkert. Kua hadde sagt koko. Og det for meg!

Ludvigs er den første restauranten jeg kan huske å ha vært på. Den lå i Torggata, men er for lengst borte.

Seinere har jeg spist middag med alle jeg virkelig er glad i, i den samme lille veistubben. Torggata. Min gamle onkel pleide å ta meg med til "Kineser´n", eller Taste of China som den het, sjappa med byens beste Dim Sum og rask servering og ikke så gærne priser heller. Onkelen min pleide å spørre om planer og fortelle om ideer og oppføre seg perfekt og upassende, akkurat sånn som onkler skal, mellom massevis av munnfuller av deilig klissete mat. Nå er Kinesern borte, men det er onkelen også. Så for min del kan det være det samme.

Da jeg gikk på videregående var Elvebakken en skikkelig yrkesskole, hvor folk gikk i arbeidsklær og skulle bli tømrere og mekanikere og hjelpepleiere og sånt (pluss de som gikk på Tagging, form og farge, men de var alltid litt annerledes). Kantina var ålreit, altså, men i lønsjen gikk vi til Torggata.

Hadde vi penger dro vi på Marinos, de hadde shish kebab av (faktisk) høy kvalitet. Dessuten en sånn spilleautomat som vi syntes at vi pleide å tjene penger på, sjøl om vi helt sikkert stort sett tapte.

Når vi ikke hadde penger dro vi på Go-go kebab. Sjappa vegg i vegg. Slagordet var Byens "beste" og billigste (sannsynligvis hadde de satt gåseøyne rundt beste i et fåfengt forsøk på å slippe unna Forbrukerombudet eller noe sånt), og det var et pitabrød med masse kjøttdeig og dressing i. Jeg tror det kosta tjue kroner, og vi blei stapp mette, alle sammen.

Da jeg vokste forbi kebaben og fant det nødvendig å invitere folk jeg likte veldig godt (og gjerne ville bli enda bedre kjent med) på restaurant var det bare å gå rundt hjørnet, i en eller annen retning. I Bernt Ankers Gate var Saigon. I Osterhaugsgate ligger Dalat. Begge vietnamesisk, billig, dritgodt, og med såpass dårlig standard på lokalene at vi aldri ble plaga alt for mye av tilreisende mat-orientalister fra Oslo vest.

Og jaggu, nå som jeg er blitt voksen (og vel så det, vil de strengeste si), har Habibi, den utmerkede palestinske restauranten som pleide å ligge i Olav Thons nå nedrivi bygård i Storgata, opp til Strøget-passasjen.

Hvorfor spiser man andre steder enn i Torggata, egentlig? Det har jeg aldri skjønt.

Det er klart, sentrum er mer enn Torggata. Sentrum er den svinge-veien fra legevakta til Blåkors, der hvor det alltid er så mørkt om kvelden og politi alltid ser stygt på deg. Sentrum er på baksida av den svingen, ut mot Akerselva, hvor Oslos kanskje aller mest klassiske stykke graffiti, en tegneserie-burner signert Mack&Bits i 1991, fortsatt står. Den blir svakere i fargene for hvert år. Men ingen maler noe nytt over, for Sentrum respekterer Mack og Bits.

Sentrum er Karl Johans gate klokka fem om natta, hvor det er så lite folk at man lurer på om man er på filmopptak i en falsk by hvor ingen egentlig bor, før man sjekker klokka og skjønner at man er den eneste som ennå ikke har lagt seg.

Sentrum er Solli Plass, hvor man kan dra en lørdagskveld for å bli kvitt fordommer, og ende opp dynka i dyr sjampanje og jævla irritert på dumme spradebasser med dyre sigarer og irriterende bra drag på det til enhver tid ønskede kjønn.

Sentrum er de stille gatene ned mot Akershus festning, hvor man ikke kan stoppe på rødt lys hvis man er aleine i bilen. Ikke fordi man er redd for å bli rana, men fordi man er redd folk skal tro man er en sånn som mener damer kan kjøpes for penger.

Sentrum er Galleri Oslo, det tåpelige, mislykka kjøpesenteret som i et anfall av frykten for å være provensiell, ble bygget med små møteplasser oppkalt etter internasjonale storbyer. Her kan du slappe av og ta en kaffe i Tokyo. På denne vonde marmorklossen, liksom. Og ved siden av Galleri Oslo, Vaterlandsparken, som peker så praktisk direkte mot Mekka, om noen av byens mange muslimer skulle være i nærheten og ikke ha et bedre sted å be.

Sentrum er sjukt mange bysykkelstativer. Sentrum er parker man kan ligge nesten naken i, så lenge man ignorerer at noen på naboteppet røyker noe de strengt tatt ikke burde.

Sentrum er det beste og det verste i byen. Lite midt i mellom. De rikeste bor her. Og de fattigste. Men middelklassen, den bor andre steder. Sentrum er kultur og ukultur. Byens beste og verste musikere. Byens beste og verste danseplasser. Sentrum er stedet for løpeseddelutdeling mot G20-toppmøtet i 2019, og demonstrasjonene mot de rasistene som skal arrangere det møtet til høsten. Sentrum er PR-konsulenter, men også rusomsorgen. Rike folk som skal i møter, fattige folk som skal kaste bort noen timer.

De fleste av timene mine har jeg kasta bort i gatene rundt Torggata. Der har jeg jobba, spilt inn plater, gått på skole, demonstrert, planlagt aksjoner, klistra plakater, jeg har sykla og trent og solt meg og festa og flørta og liggi og grini og driti meg ut. Gang på gang, gjennom en mannsalder. På snaue 800 meter.

Jeg er ikke der alltid altså. Det hender jeg beveger meg ut. Til andre deler av byen og andre deler av sentrum. For å gjøre de tinga man må gjøre. Og jeg skjønner at andre folk ikke elsker Torggata på samme måte som meg. Jeg skjønner at folk ikke ser estetikken i plakatveggen på den rivningstomta ved politistasjon rett ved Youngstorget. Jeg ser at folk ikke har dansa i fontena på 1. mai siden de var ett år gamle. Og jeg skjønner at noen folk sikkert synes det er irriterende med alle de blomsterhandlerne på Stortorget, eller at Domkirka tross alt ikke er like fin som den i Trondheim.

Men det er én ting jeg ikke skjønner.

At folk vil spise mat andre steder enn i Torggata. Det er fuckings utrolig hva mennesker får seg til å gjøre.

Difficult living conditions in the inner cities is not just a modern day challenge. In his study of the working class in Christiania in 1858, Eilert Sundt expressed a well-known ambiguity about life in the big city, describing the city as both “the cave of vices” and “the hotbed of the civilization”. Even though we may use other terms today, we will recognize his sentiments. Today's newspaper headlines, as well as our own experiences, are often characterized by such contradictory images of life in the big city, and it is well documented that it is within the largest cities we find both the most privileged and the least privileged groups. It is especially in the capital that social differences are evident, illustrated by the fact that Oslo has been divided throughout much of its history. In the collective work “The History of Oslo City”, chapter four is entitled “The Divided City”. Here, Knut Kjeldstadli depicts how Christiania was not one city in the beginning of the 20th century, but two. The west side was the home of the most privileged, i.e. middle and upper classes, while the working class would reside on the east side (Kjeldstadli, 1990).

But although the city's division is remarkably stable, it is not completely static. Some areas in the west, right by The National Theater, have changed character. The areas Vika and Ruseløkka used to be called Piperviken and Ruseløkbakken in the mid 1800s, and were poor working class areas at the time (Sundt, 1858/1975). Since then, houses have been demolished, new constructions have been raised and the area has been extensively renovated. At present day they are prosperous parts of the inner city.

Grünerløkka, Kampen, Rodeløkka and several neighbouring areas on the east side, have also gone through major changes in the last 30 years. They have changed character from working class areas to middle class areas where the new residents have significantly higher education and income. The areas have undergone so-called "gentrification", which can be described as a process of renovation of deteriorated urban neighbourhoods. New residents refurbish homes and outdoor spaces, thereby attracting more people with similar interests. Simultaneously, shops, restaurants and services change in line with the new residents' wishes and requirements. Coffee shops, galleries, brokerage firms, shops and restaurants pop up, and target a young, urban middle class, while the “old” pubs, "ethnic” shops and affordable eateries are getting fewer. Due to gentrification it is becoming more difficult for low income groups to buy an apartment in the central urban areas, which have now become pressure areas in the housing sector. Consequently, the exclusion of residents with low or normal income from the inner city areas is a challenge for Oslo. How do we ensure that the inner city continues to be diverse in the future?

Stortinget station has been named after the Norwegian parliament, “Stortinget”, situated imposingly in the heart of the city. But how has the supreme arena for political debate and decision-making in Norway related to the capital itself?

The need for separate urban policies were long neglected in a political climate with a strong focus on the regions: “In Norway the regional policy has had a hegemony which has not been seen in any other northern European country, whereas a national urban policy has been almost absent” (Knutsen 2015, page 21). It has not been legitimate to develop a separate urban policy, which to a certain extent is related to the quite strong emphases of geography versus population in the parliamentory seats at “Stortinget”. In spite of an adjustment ahead of the parliamentory election in 2013, where the increase in population in Oslo and Akershus, Rogaland and Hordaland made these three city regions stronger represented, is still particularly the Oslo region underrepresented compared with a distribution of seats solely based on the population.

However, there has been a change in this field over the last decade. More voices claim that a national urban policy has been legitimized by the threat of climate change; we must live closer and decrease the need for transportation or turn the direction towards less emissions. Others claim that this started a bit earlier. This imbalance was underscored in the Whitepaper nr. 31 (2002-2003) with the title City report. About the development of an urban policy. The content of this paper made the need of developing a separate urban policy unequivocally unclear.

The capital has also received its own report, that is the Whitepaper nr. 31 (2006-2007), An open, safe and creative capital region. Report from the capital. As the title indicates, the report stresses the role of Oslo as capital and the biggest city, in addition to governing challenges in the city region and the particular challenges of Oslo as a major city. Among the latter mentioned, integration and inclusion are empasized, as are also differences in living conditions, a safe city, public transport and the ripple effect of extensive state property and activity in the capital. Furthermore it is argued more explicitly than earlier not only for an urban policy, but even for a particular capital policy.

In the so far last Whitepaper with an urban focus, that is the Whitepaper nr. 18 (2016-2017) Sustainable cities and strong districts, the principle of sustainability stands strong with the slogan “city and countryside, hand in hand.” At the same time it states the “particular challenges in the region of the capital”. However, it can be discussed how strong the explicit focus on the cities really is in this document, and now returning to where we started above, it seems like the consideration for the districts again overshadows the need of attention to the capital and the major cities.

“Good night, dear Oslo!”, the songwriter Lillebjørn Nilsen sings, “while the Freia-clock blinks quarter to one.”

The Central Station (Jernbanetorget) is situated in the middle of the city, and in many ways it is the heart of the city. Here everybody gather while passing by - rich, poor, young, old, tourists, commuters, those who have lived here for generations and those who just moved here from Molde or Mogadishu. Try and sit down on a bench and watch; the diversity is fascinating.

Oslo houses the wealthiest and most highly educated inhabitants of Norway - and those who struggle with the biggest challenges related to drugs and mental illness. Here are both the most expensive houses and the longest waiting lists for public housing. In Oslo you will find the richest and the poorest, the best possibilites and the greatest challenges. As one of the leaders of a municipal unit in Oslo put it: “The worst cases end up in Oslo” (Brattbakk, with others 2016) but at the Central Station they were not allowed to be.

Oslo and the bigger cities have a higher share of disadvantaged people than you would find in other kinds of municipalities in Norway. That alone is nothing new, and the cities are to a certain extent finacially compensated for the higher pressure this causes for the welfare services. However, the state doesn't explicitly take into account the higher expenses for social housing when the resources are distributed. With “disadvantaged people” we mean those who are financially disadvantaged, like poor people living alone and poor families with children, often with background as refugees, and socially disadvantaged, like drug addicts, persons with mental illness and persons with a criminal record that makes it difficult to find a place to live. In combination with a strong growth in population over time and a crowded own and rental market, the high proportion of disadvantaged leads to some specific social housing challenges in the capital.

As a consequence of the idea that as many as possible should have their own housing now - a goal which in itself is worthwhile - the number of people not being able to get their own housing has increased. To people with challenges related to drugs or mental illness, the decline in institutions leads to a greater need for specifically adapted housing and close social follow-up. This includes for example reinforced apartments for persons with “a rough way of living” and housing which is facilitated for follow-up services and social staff.

Many points to a quite significant need for more and better adapted municipally available housing, and analyzes are showing that the cities have higher expenses per citizen related to the department of social housing than other kinds of municipalities in Norway (Brattbakk, with others 2016). In particular the older apartment buildings in Oslo stands for a high concentration of social housing. These apartments are badly suited for many of the new needs for social housing, and they are expensive to rebuild. The high price level in Oslo and the bigger cities contributes to higher municipal expenses when making available suited social housing for disadvantaged groups.

A reinforced supervision of the living environment and singular residents could have lead to far less wear and tear on the municipal housing stock. And even more important, given all the residents, including kids and youth, living here and in the neighbourhood; better grow up conditions.

Many key professionals within the field of social housing are pointing at the importance of a more explicit consideration of social housing needs when new housing estates are built or developed. This may contribute to lower socio-economic and ethnic segregation and create better living environments. However, in reality it seems often demanding to include these kind of perspectives in the overall planning, and political will and instruments to ensure a good mix of housing types and ownership forms also seem to be absent when new areas are being developped. As an example you may ask why the new “Fjord City” (Fjordby in Norwegian) does not include any municipal housing. It's being built right now, just a stone’s throw from the Central Station.

En fortelling fra Gamle Oslo av Heidi Marie Kriznik

Tid på Tøyen, tid for Tøyen

Kafébordene utenfor Munchmuseet er blanke i sola, metalliske sirkler som blender øyet. Jeg har funnet et ledig bord, rett ved siden av meg sitter det tre damer. Jeg visste hvem den dama var, sier den ene. Har du ikke fått det med deg? Hun pleide å sitte på kafeen borte i gata her. Og nå er hun død. De tre damene har nøkkelkort rundt halsen, kanskje arbeider de i nærheten, kanskje har de for vane å spise lunsj ute, på en av Tøyens kafeer. Er hun drept? Det er forferdelig. Damene nikker, gjentar det forferdelige ved at et menneske de gikk forbi og en gang iblant satt ved siden av, er drept. Når de drar hjem er det ikke til den kommunale gården der dama ble drept, der det bor over seksti unger. Bakken er våt etter nattas regn, og asfalten er dekt av rosa blomster fra kirsebærtreet, de fester seg til sålene på skoene når jeg reiser meg og går. Jeg snur meg og ser mot Munchmuseet, arvesølvet som ble solgt, bytta, snart flytta. Servitøren tørker av bordet jeg satt ved. Nå er det klart for noen andre. Foran meg på fortauet går det en gutt sammen med det jeg regner med er mora, gutten drar i moras hånd. Jeg er rett bak dem. Hva er fem minutter? sier gutten. Tiden det tar å gå dit, til T-banen, sier mora. Men hva er tid? Det er ikke langt hjem, sier mora. Langt for noen, tenker jeg. For det var flere som mente det var så langt hit at få ville komme for å se kunsten på Munchmuseet. Gutten vil hjem, så vil han brått leke på lekeplassen. Han slipper moras hånd og løper. Tiden, stedet og handlingen kan ikke skilles fra hverandre, jeg veit ikke hvorfor jeg tenker på det nå, det er en setning jeg har fra et dikt. Gutten er i toppen av klatrestativet. Underlaget på lekeplassen er nytt, sklia og klatrestativet også. Kom! roper mora. Nå er det hun som vil gå. Men gutten vil ikke komme, han vil bli. Ved den overfylte søppelposen rett ved har ei kråke fått tak i en potetgullpose, kråka har hele hue inni, får tak i chipsbiter, rester. Innsida av potetgullposen er sølvfarga, blank. Du er mammaen til Linnea sier ei jente ved siden av meg. Jeg kjenner henne igjen fra Tøyen skole, hun går i klassen over Linnea. Hvor er Linnea nå? sier jenta. Jeg er på vei for å hente henne på skolen, sier jeg. Kommer hun hit? sier jenta. Kanskje, sier jeg. Hvorfor kanskje? Kom, roper mora til gutten, og jeg snur meg dit. Gutten henger etter mora, nå er det hun som drar han i armen. Hvorfor kunne de ikke være her? Jeg blir stående og se etter dem. Skal du ikke gå og hente dattera di og komme hit? sier jenta. Jo, sier jeg. Så kom da, sier hun. Kommer du?

Om kvelden er jeg frivillig på et breake- og jammearrangement og står i døra på Biblo Tøyen, jeg skal passe på at de som ikke skal breake tar av seg skoene og at de som skal breake får blå skoposer utenpå skoene. Mange barn står utenfor og venter, flere har stått der i over en time, helt siden Biblo stengte. De står der enda det regner, og er kaldt. Flere banker i de store vindusrutene, en og annen roper. Hvorfor er det ingen som åpner? Skulle det ikke begynne nå? Barna får ingen forklaring. Noen av dem drar i døra, men døra er stengt. Så smeller det brått mellom to av ungene, de slåss. Flere henger seg på. Hold dørene stengt! roper en voksen på innsida. Jeg gjør som han sier. Han ringer politiet. Dørene til Biblo åpner ikke. Politiet kommer, barna som var innblanda løper vekk. Og da åpnes dørene. Det er nesten tjue minutter for seint. Barna trenger seg på, de er mange. De fleste barna er der uten foreldre. Ei jente kommer med mora si. Jeg sier til mora at det er skofri sone på Biblo. Jeg peker på skoene til dama. Fint om du tar dem av, sier jeg. Det tør jeg ikke, sier dama. Er du redd du ikke skal finne dem igjen? sier jeg, og det er forståelig hvis hun tenker sånn, det er mange sko. Du får sette dem litt for seg sjøl, sier jeg. Jeg vil ikke at skoene mine skal bli stjålet, sier dama da. Mine sko har aldri blitt tatt, sier jeg. Jeg setter alltid skoene mine her, sier jeg. Og hva slags sko har du? sier dama. Det tar litt tid før jeg skjønner hva dama mener. Jeg står i sokkelesten. Hun veit ikke hva slags sko jeg har. Er skoene dine så dyre? sier jeg. Ja, sier hun. Da får du slutte å ha med deg så dyre sko hit da, sier jeg og hadde jeg vært femten år ville jeg ha dytta til henne, kanskje slått, starta en slåsskamp, slåss til politiet kom. Men jeg er ei dame på over førti, så jeg gir henne skoposene, de som var forbeholdt breakerne, så hun kan ha dem utenpå de hvite og svarte Adidas-ene sine.

Et av områdene i Biblo er avstengt, der er det ikke lov å gå, og det dama med skoene som påpeker det, at det er en gutt innafor sperrene der, hun peker på gutten. Jeg går bort til han, for å si i fra, for å gjøre som dama forteller meg, og holde reglene vi har blitt satt til. Men jeg er ikke glad for jobben jeg har fått. Hei, sier jeg til gutten. Så du meg hele tida? sier han. Nei, sier jeg. Hva ville ha skjedd hvis dere låste meg inne og jeg ble her i natt? sier han. Det er et bra gjemmested, sier jeg. Hvorfor skulle jeg gjemme meg? sier han. Nei, hvorfor skulle du gjemme deg? sier jeg. Og han sier: Jeg skulle bare teste om dere fant meg, eller merka at jeg var borte.

The eastern part of the neighbourhoods downtown has been a working class district since the 19th century and way back from the 17th century these areas have been predominantly characterized by poverty and new arrivals. Furthermore Grønland has been a major approach road to Christiania (Oslo) with its Vaterland Bridge, accommodating a number of inns and taverns and a lot of trade. A lot of travellers who could not afford or obtain a permission to spend the night within the city limits settled here with its centralized and suburban status. Lying just outside the city limits, the street structure and buildings in Grønland did not display the characteristics of a strictly regulated area. In addition to accommodating many poor families, open public spaces and the buildings themselves were physically characterized as belonging to the lower classes outside of the city limits. In the 1920s, Signy Arctander at the Central Bureau of Statistics in Norway claimed that the eastern urban areas still had major social challenges and were poor areas for growing up and that the authorities had to do something about the city’s major social inequalities. This reality is not only history.

Norway’s most important public transport hub for trains and buses is located very near to Grønland today. An extensive number of public and private institutions, a busy business community of trade, dining places and nightlife, a diverse range of religious congregations and treatment facilities for vulnerable groups, makes this area buzz with people around the clock. In other words, Grønland is largely influenced by all those visiting and staying there to work, shop, go to a cafe or pub, get treatment, buy and sell drugs, beg, seek services, go to the mosques and churches, participate in organizations, participate in different forms of culture or simply hang out with friends in one of the area's many small and large public spaces. For many, Grønland is just "home", and not necessarily an urban, vibrant or "exposed" urban area.

Yet, as suggested above, it's still a part of Oslo which is often mentioned in sentences next to the word “challenges”. The 1920s is not the only moment when researchers expressed their concern. In more recent times, researchers and public authorities have designated the inner eastern area as a district in which challenges regarding a variety of living conditions keep accumulating. Efforts to remedy these districts have been put into effect through the public initiations of urban renewal projects in several phases since the 1970s. As of 2017 a new round of urban renewal is being planned in Grønland. Indeed, the living conditions for the area as a whole are improved and outdoor areas and housing is upgraded through previous investments. Nevertheless, a major part of the improvements are due to a "gentrification processes" and, first and foremost, through changes in the composition of the population and in the local businesses. Even so, a relatively strong acculumation of challenges in living conditions are still to be found in parts of Grønland and this is one of the areas in Oslo which score lowest in a number of indicators such as employment, poverty, public health, digital bullying and, not least, evident drug dealing. This provides very special conditions for Grønland as a place and local community, and in combination with widespread poverty among families with children, there are some very specific challenges for local children and youngsters growing up in this environment. However, whether it's because of, or in spite of these challenges, a lot of people do like Grønland. As a young man said; "Grønland is my place, here is where I feel at home."

Tøyen is centrally located in the city and has a diverse population, a variety of private and public services, a rich cultural life, and a mixed composition of houses and buildings. In addition to the complex group of residents, the area is highly influenced by anyone who visits and stays there to work, go shopping, go to cafes or pubs, get treatment, buy and sell drugs, beg, go swimming, go to mosques and churches, visit the library, play football, participate in organizations, engage in cultural activities of various forms and much more.

A lot of people also come to Tøyen to visit the Edvard Munch Museum. This shall continue only until 2019 when the museum moves into a new building in Bjørvika downtown. In May 2013, the City Council adopted the “Munch agreement”, which included, among other things, an “urban renewal program” for Tøyen in the five-year period 2014-2018. “Urban renewal program” is a method and a development program for implementing comprehensive efforts in areas with exposed living conditions. The “Tøyen Initiative” can be seen as a compensation for the loss of an important national and international art institution. What will be Tøyen’s pride in the future, when the Munch Museum is gone? Perhaps it could be the residents themselves and their involvement? The local efforts have flourished in recent years, and many new organizations and teams have seen the light of day. The “5-årsklubben” (The 5 year-olds-club) has done a lot to strengthen the relationship and contact between the preschool children and their families and the school. With the establishment of Tøyen Sports Club, the area has acquired a long awaited sports club that has in a very short time been able to create a wide range of activities, with low membership fees and an incredible membership growth. The “Tøyen Ravens” consist of local adults who walk the streets on Friday and Saturday nights all year round and contribute to security and neighbourhood affiliation. “Tøyen Unlimited” is a neighbourhood incubator that engages in social entrepreneurship. Local people with good ideas for how to solve small and big challenges for residents in the neighbourhood are financially supported and receive knowledge and guidance.

The Tøyen neighbourhood is in the middle of a process called "gentrification". Gentrification is a socioeconomic transformation of neighbourhoods, characterized by the the middle-class setteling in older, often working-class areas, with the effect that the area is renovated physically, socially, culturally and commercially to meet the needs and interests of the new residents. On the positive side, there is an upgrade and supply of resources to the area, whereas on the negative side there is a risk that this will push out the most vulnerable groups from the district since housing costs will get too high and there will be fewer private and municipal rental homes available. Still today, Tøyen has a mixed population, where a lot of residents with high education and income live side by side with the strongest concentration of poor families in Oslo. But what will the situation be in 10 years? Will the economically weak be squeezed out? And what kind of city will we get if all the central areas of Oslo will be only for those with the thickest wallet?

Ensjø is a district in the borough of Gamle Oslo (Old Town) and is located about 2 km east of Oslo city center. The area borders with Tøyen, Kampen, Vålerenga and Hovin, and is known for brick and tobacco production in older times and more recently for car dealers. Ensjø currently undergoes a comprehensive transformation process, in which the entire area changes its character. The name Ensjø comes from the farm Ensjø, which until the 1830s was called Nedre Valle. The other 19th century farms in the area are Malerhaugen and Grønvoll.

At the end of the ice age, the Oslofjord's coastline reached as far as Ensjø. According to Wikipedia, the deposits from the water and soil were used to start the production of bricks here in the 19th century. The area had two brick manufacturing workshops and in 1875, Nitedals Match factory (closed in 1967) moved the production to Ensjø. Tiedemann Tobacco factory was also at Ensjø. The factory finally closed in 2008 after 230 years of activity, marking the disappearance of the last tobacco production in Norway. Ensjø, together with Kampen and Vålerenga, were also home to many industrial workers, and several major workers' riots took place here in the late 19th century.

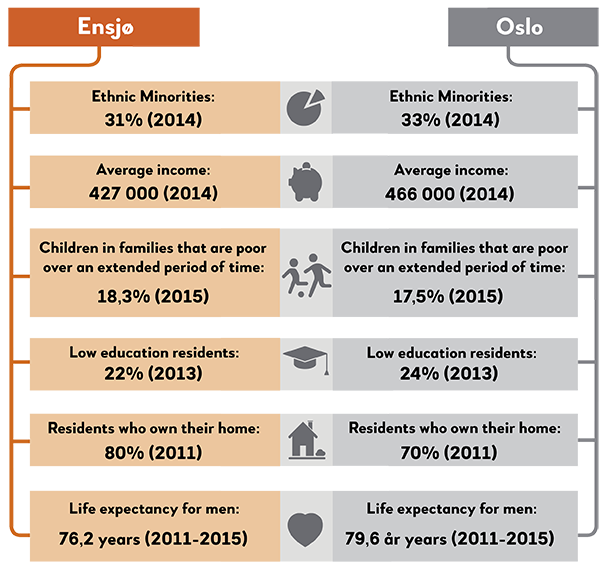

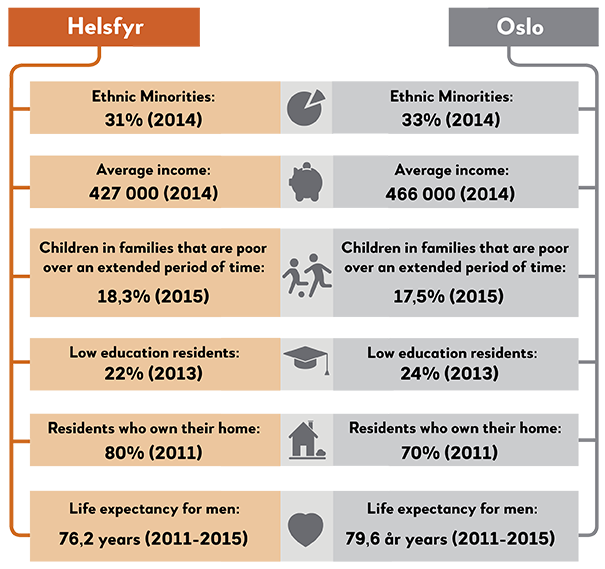

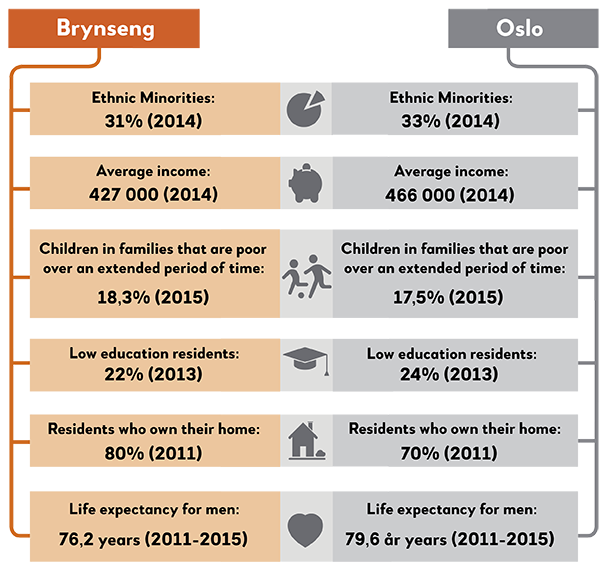

Recently, Ensjø is more known for housing construction projects as well as for its many car dealers. There are about 1400 households in total at Ensjø, a combination of villas and apartment complexes, many of which were built in the 1930s. Ensjø is currently in the middle of a major transformation as part of a compact urban development, where the inner city of Oslo will be developed into an urban area running through Hovinbyen towards Grorudsdalen. As a result of this the neighbourhood Helsfyr, to which Ensjø is a part of, has had a very high population growth rate of 25 percent over the past five years. Helsfyr neighbourhood belongs to the Gamle Oslo (Old Town) borough, and scores higher on almost all living conditions indicators, especially the proportion of poor and expected life expectancy, than the rest of the borough. At the same time, the neighbourhood generally scores quite the same as the average in Oslo, but has a slightly higher proportion of people who have not completed upper secondary education, a higher level of cramped housing and disabled people, and a little lower proportion of poor and unemployed people. The presence of ethnic minorities is significantly lower than the rest of the borough, and slightly lower than the average in Oslo.

Fjørstad (2015) has studied the overall plans for the area and interviewed families with children, who have recently moved into the two new housing projects in the area, about how they evaluated the quality of their living conditions in the area. She concludes as the following: "Residents knew that the planning of Ensjø lacked quite a deal and that it lacked urban places like cafes and restaurants and other social venues. It may seem like the planning has had too much focus on housing and green spaces, and forgotten other elements needed to create a new neighbourhood in Oslo's inner city. The residents did not conceive Ensjø as an urban area, and were worried that Ensjø would become a sleepy suburb with nothing happening in the evenings."